Going Dutch in Elmina

Slave castle

(zie Nederlandse vertaling)

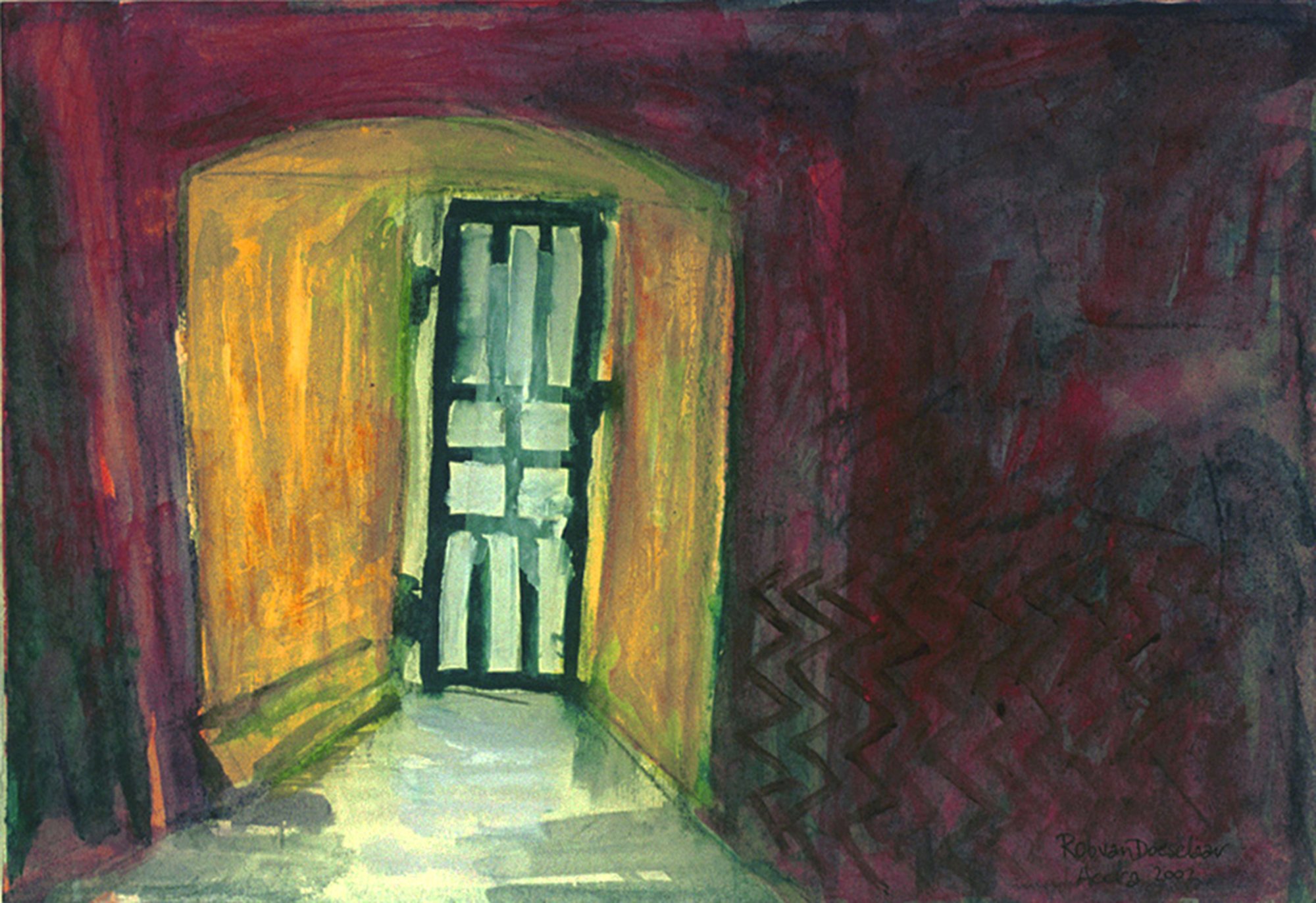

Following the coastline from Cape Coast to Elmina, I drive on a rather straight road. On both sides I see rows of palm trees. On my left, the surf hits the beach forcefully. On my right, there are some thatched huts and houses. Far away I see the white castle, like a big cruise ship beached on the rocks.

The vivid town of Elmina is made up of only a few streets - yet I was delayed by a traffic jam in the main street. Eventually I reach a blue painted iron bridge, which looks more important to contemporary Elmina than the nearby castle, which only attracts foreign tourists. To the right of the port lie coulorful, painted fishing boats. On the other side is a market place. On a nearby hill, another white fortress can be seen. Possessed by the Dutch, it was used to defend Elmina Castle. Some palm trees, planted near the entrance, look as if they are watching the castle. They move gently in the wind. The roar of the sea drowns their rustling. I look at the mighty castle. This spot calls for serious questions, especially for me as a Dutchman.

Elmina Castle is the oldest European building in sub-Sahara Africa. The exit used to be at the seaside where the slaves made their way to the evacuation ships. On the ground stands a little signboard "slave exit to waiting boats", carelessly placed against the wall, as if you could put it anywhere.

Elmina Castle must have been the last memory of Africa for the slaves who were transported away. Nowadays the United Nations has adopted Elmina as a protected World Cultural Heritage site. Ghana cherishes it as a major tourism attraction. The Netherlands sees it as its moral duty to preserve the castle.

In the courtyard of Elmina Castle I hear only the sea's noise and distant sounds from the little town. Nothing beyond that. No rattling of chains, no cracking or lashing of whips, no shouting of drunken soldiers, no moaning of the sick. Everybody and everything from the past has fled. I don't smell anything particular in Elmina Castle: No rotting, no urine, no excrement, no sweat, no burning. It is as if all the misery has been taken away. The thick walls don't leave us any history.

A cash desk has been placed within the castle, and around the building are distributed a few simple signs, like "slave exit to waiting boats" and "male dungeon". On the second floor a souvenir shop has been established where I can buy postcards, place mats, fabrics, drums and some books related to the castle, slavery and Ghana. The little museum - in the former chapel - gives information about Ghana and its cultural traditions. I don't discover much about the slave trade there. The old cannons on the roof are exposed to view. I wonder if they have ever been fired. The building radiates something unassailable. The Portuguese, The Dutch and the British never got a hold on it. What is Elmina Castle's secret?

The slaves are gone. The tourists and the guide take their place. Their presence helps me imagine how hundreds of them would have been held prisoner in such a small place. The tourists look around, into all the barren corners. I form a part of the images they try to create for themselves. In the dark dungeons downstairs, the most dramatic spaces of the building, we all become silhouettes, making it easier to imagine ourselves as slaves. What does this create in the mind of the African-American with the white baseball cap in front of me? How does he regard our piece of common history? Does it give reason to hate? What does the big Australian woman, walking next to me, think? Perhaps her ancestors were also deported. So many people bear scars from history.

In scale, the tragedy of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade is comparable to the Nazi Holocaust; maybe even greater. I may sound incredible, but we don't know exactly how many million slaves were traded. After all, during those centuries it was normal to sell slaves to the Americas. In the end, even horrors become commonplace when repeated daily. Our endless ability to adapt can be frightening sometimes.

When a cargo of slaves left Elmina Castle it was by boat to the Americas. In some cases, more than half of the slaves perished. For me, as a spoiled European living around the year two thousand, it is impossible to feel the harm people did to each other. Not only did the slaves live in miserable circumstances; the European crew itself often fell ill and died in huge numbers. Why this madness? All because of the concept of progress? What progress?

The dead cannot be brought back to life. The transported slaves cannot return. Their descendants do not want to come back. It is impossible to imagine what the world would be like if the slave trade had never happened.

Growing up, I learned that I could be very proud of my country, the tiny Netherlands, one of the most thriving nations of the 17th century. Nowadays, we are still proud: of our tolerance, our productivity, our social security system, our pacifistic tradition and our conscientious morality. At school, I was taught our history, the achievements of our naval heroes and the flourishing cities in the 17th century. We admitted hundreds of thousands of religious refugees from other European countries. Because of that, Amsterdam became a great city. Peter Stuyvesant did not conquer Manhattan; no, he just bought it from the Indians. We never used violence to impose on people. We did have some colonies, but for the sole purpose of doing business, not to expand our political power or propagate Christianity. We just wanted to make money by buying items in one place and selling them somewhere else at a profit.That was all. And there was nothing wrong with that. That's what I was taught.

Nevertheless, just on top of the entrance of Elmina Castle, I see a Dutch lion painted with his sword at the ready. In his other paw he is holding something that looks like a bundle of paper. The lion walks on two legs, like most lions on European escutcheons. Strange, that a European country uses an African animal as its symbol. And it is even more curious to see the symbol of my own country back in Africa.

We all carry our history with us, even if we do not know about it. I cannot ignore the facts in which my ancestors have played a role, although it is more than 150 years ago. Even if I forswear everything, I will still be identified with them.

In Elmina Castle, it becomes clear to me that something has gone wrong in the teaching of Dutch history, because the Dutch stayed more than two hundred years on the Gold Coast for the sole purpose of exporting slaves - for a profit. Apparently, we have difficulty in describing this shameful part of our history.

The scars of the slave trade will not disappear in the near future. Our collective memory is very strong and mourning takes its time. And we cannot just start from scratch, as we would in a game. So when will we come to terms with it? After we stop denying the historical facts? Or perhaps only after we learn mutual respect and trust.

Rob van Doeselaar

Accra, March 2002